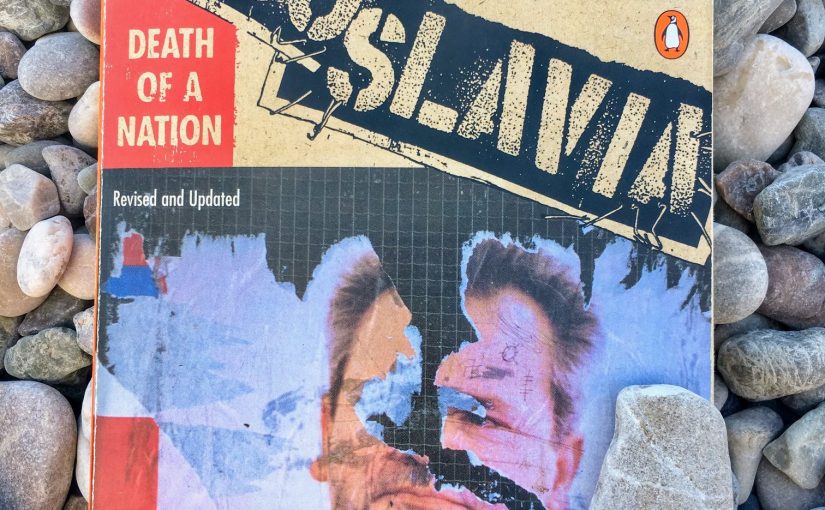

The bitter history of Old Europe must never repeat itself. Yugoslavia: Death of a Nation by Laura Silber and Allan Little is one of the most acclaimed books on the violent dissolution of the former European federation.

Penguin Books has published and republished it several times. I am handling a copy of the updated 1997 edition. I’d like to quote a few fragments:

1.

It is difficult to imagine a slogan more likely to rile the Serbs than the speech made that night, at Cankarjev Dom [convention center], by Jože Školjč, then head of the Slovene Youth organization. “Albanians in Yugoslavia are in a position similar to that of the Jews in World War Two.” For Serbs, this struck at the essence of their rekindled mythology: they were the martyrs.

On February 27, speaker after speaker in Ljubljana condemned the Serbs for repression in Kosovo. Belgrade had become the tormentor. “Yugoslavia is being defended in the Trepča mine. The situation in Kosovo shows that people are no longer living together but increasingly against one another. Politics cannot be pursued on the streets or when lives are put at risk,” said [Slovene leader Milan] Kučan.

“The Trepča miners are defending the rights of citizens and Communists in Kosovo to elect their own leadership. Slovenes are not casual visitors in Yugoslavia. We helped create it and are responsible for its future. We protest against fanning the psychosis of the state-of-emergency. We are warning that a quiet coup is taking place before our eyes which is changing the face of Yugoslavia.” [pp. 65–66]

2.

Within the Serb leadership in Croatia, [extremist leader Milan] Babić now led an assault on [relatively moderate rival] Rašković. By now he was number two in the SDS [ethnic Serb party] hierarchy, and Mayor of Knin. He began by building an alternative power-base […]. In May, he established the Association of Serbian Municipalities [that later became the breakaway Republic of Serbian Krajina, with its capital at Knin]. One by one, Babić toured the areas in which the Serbs constituted a majority of the population. By mid-summer a handful of local municipalities neighboring Knin had signed up to his Association: Borovac, Dvor, Vojnić, Donji Lapac.

But by no means all the Serb-populated areas backed Babić’s rebellion. Many were interested in dialogue with Zagreb, and were far from hostile to the new government. In those areas, Babić used force to impose his authority. [p. 97]

3.

As the tanks rolled through the streets, the police raided and shut down the liberal radio station, B-92, and Studio B, the only Belgrade television station not in government hands, which were both reporting the demonstration. “The leadership of Serbia requested the dispatch of Army units since the majority of police units are engaged in Kosovo,” said a statement from the Federal Presidency, explaining why the JNA [Yugoslav army] was called instead of the police. [p. 121]

4.

[Defense minister] Kadijević did his bit by conjuring up nightmarish images from Second World War. “In Yugoslavia all possible enemies of socialism and united Yugoslavia have emerged on the scene, Ustaše, Chetnik, Albanian, Beloguardist and other factors. We are fighting against the same enemy as in 1941.” [p. 125]Shkurtegëza për këtë postim: https://pli.si/2oEi3lI